Now that we established what money actually is is and what it costs us, the next question beckons: where does it come from and how does the monetary system actually work?

The source of money

Where does money come from? Where is it actually created?

I’ve posed this question to a lot of people. It’s a hard one. I’ve even had a discussion with a banker and an economist about it and neither of them could actually answer it. Not for want of trying. But every time we came to the point where I wanted an answer to what the actual source of money was, where new money comes into existence, I got a blank.

Part of the money is created by government through the central banks but this is only a very tiny fraction, about 3% in our current day economy. The vast majority of the money that is created today comes from private banks and it is created from debt … out of nothing. That means that in today’s world, private banks hold the power to create as much or as little money as they see fit. And that power has minimal limitations.

You might think that in order to lend money you would also need to have it in the first place. That holds true for most of us but not so for banks. For a long time I believed that banks need to hold a fraction of the money they give out in reserve, which is known in the financial sector as fractional-reserve banking. But apparently that seems to be false, at least in the UK and probably in most other countries.

This means we have to make a distinction between 2 types of money:

- ‘Real money’, which does not create debt when it comes into existence. This is the 3% of money created by governments.

- ‘Virtual money’, which is created from debt. This kind of money is called a deposit in the financial world. All the money you have in your bank account is deposit money. It is only a promise from the bank that they will pay you that money when you ask for it. It is not ‘real money’.

Both of these types of money are expressed in the same currencies however, thereby blurring which is which. From now on, I will only talk about deposit money for simplicity and because it makes up the vast majority of the money in circulation today. That means that for the money you have in your bank account, someone is in debt for it.

And since there is no regulation on how much money banks can actually create, the amount that is created is completely dependant on their mood. And that mood is influenced by their believe in the lenders’ ability to pay off the loan. You can imagine that when the economy is not doing well that trust will erode and less money will be created through lending. Less money available means less money going around and that is bad for the economy. I guess you see where this is going.

A word about interest

As mentioned before, money is largely created from debt through banks giving out loans. There is an interest on this debt, which means more money needs to be payed back than has been borrowed. Where does that extra money come from? In short, from new loans.

You might argue that it comes from value creation but value does not create money. When you bake a bread, money does not appear out of nowhere because you have created something of value. That money needs to come from an institution that can inject extra Dollars into someone’s account so he/she can then pay you for that bread. In other words, the money comes from the banks who have created it from debt. The money to pay off the interest comes from the same source.

This means that we need to inject ever more money into our economic system in order to pay of the debts. With that new money comes more debt, which means money always plays catch up with debt. There is currently about 3 times as much debt in the world as there is money.

When new money is created, new value needs to be generated alongside it in order to justify its existence. Otherwise the currency’s value would deflate. A fine example of this was Zimbabwe in the 90’s. The salary you received in the morning would not even buy you a loaf of bread by nightfall.

This creates the vicious debt cycle that holds our entire economy in a death grip of enforced growth. We need to create money to pay of the interest on the debts of existing loans. That new money creates new debts, on which there is again an interest. This cycle only pushes to problem forward in time because these new debts need to be payed off too, leading to the need of more money and thus more debt to be created. This ever increasing money generation cycle needs to go hand in hand with value creation in order to minimise the devaluation of the currency. This means our economy needs to keep growing for the system to work. When it stops growing we get something like in 2008.

The ever growing debt pool acts like a vacuum cleaner on the available amount of money, sucking it in and destroying it. With the current system, the only way to make sure there is still money left is to create more. The problem is that this also grows the debt pool, thereby increasing the power of the vacuum cleaner that sucks in the money. On top of that, due to the interest and due to the fact that new money is created from debt, we have the added problem that the debt pool is always larger and grows faster than the available money, thereby pushing our economy into obligatory exponential growth.

As mentioned earlier, this system has led to a debt pool that is now roughly 3 times as large as the pool of available money. Roughly $70 trillion in money vs $220 trillion in debt, give or take a couple of trillions. You might think this could be resolved like in the story below:

A stranger stopped in town and went into a small old hotel to check in. He asked to go check out the rooms first so, in good faith, he left a $100 bill—a deposit of sorts—with the hotel owner. The hotel owner immediately ran next door to pay his grocery bill. The grocer ran it across the street to pay one of her suppliers. The supplier used it to pay off his co-op bill. The co-op guy ran it back across the street to pay a travelling magician who had taken up residence in the aforementioned hotel for a month. The magician ran it downstairs to pay her hotel bill just ahead of the returning traveler, who picked the $100 bill off the desk and left saying that the rooms were not satisfactory.

Here, all outstanding debt is eradicated by simply circulating the $100 bill around. No one did anything, nothing was produced and no money was permanently added to the system, yet everyone’s debt is eradicated and the same amount of money that was there before is still there.

Bank debt works differently though. When you pay off your debt at the bank, both the money you use to pay off your debt and the debt itself are destroyed. Bank debt is to money as matter is to anti-matter. When they meet, nothing is left. That means that, if we pay off all the bank debt in the world, all the money will be destroyed. But due to the vast amount of debt that is generated through interest on the outstanding debt, we’d still have tons of debt left … with no money to pay it off. So, there will always be an amount of debt in the world that can never be payed off. Not because it is a law of nature but because that is the way we designed our monetary system. And that debt pool, for which no money exists, keeps on growing exponentially due to interest.

Now our brain works very well when dealing with linear growth but it’s very poorly equipped for truly grasping exponential growth and it is very hard to intuitively guess the results of it over a period of time.

This slightly altered version of the chessboard and rice fable gives an insight in just how easy it is to get it wrong when dealing with exponential growth.

Something that makes it even more clear are algal blooms. They happen when algae enter an exponential growth rate, doubling their population in mere hours. Say we have a pool with enough nutrients to sustain 1 billion algae cells. We start with 1 cell and double the population every 8 hours (which is not uncommon). After 4 days, we have about 2000 cells, after 7 it’s a million. After 10 days there are more than half a billion cells and 8 hours later there are more cells than the pond can sustain and we have an algal crash, killing off the algae due to a lack of nutrients. Increasing the nutrients a 1000 fold buys us a little more than another 3.5 days, making it basically useless.

Nothing in nature allows unlimited growth.

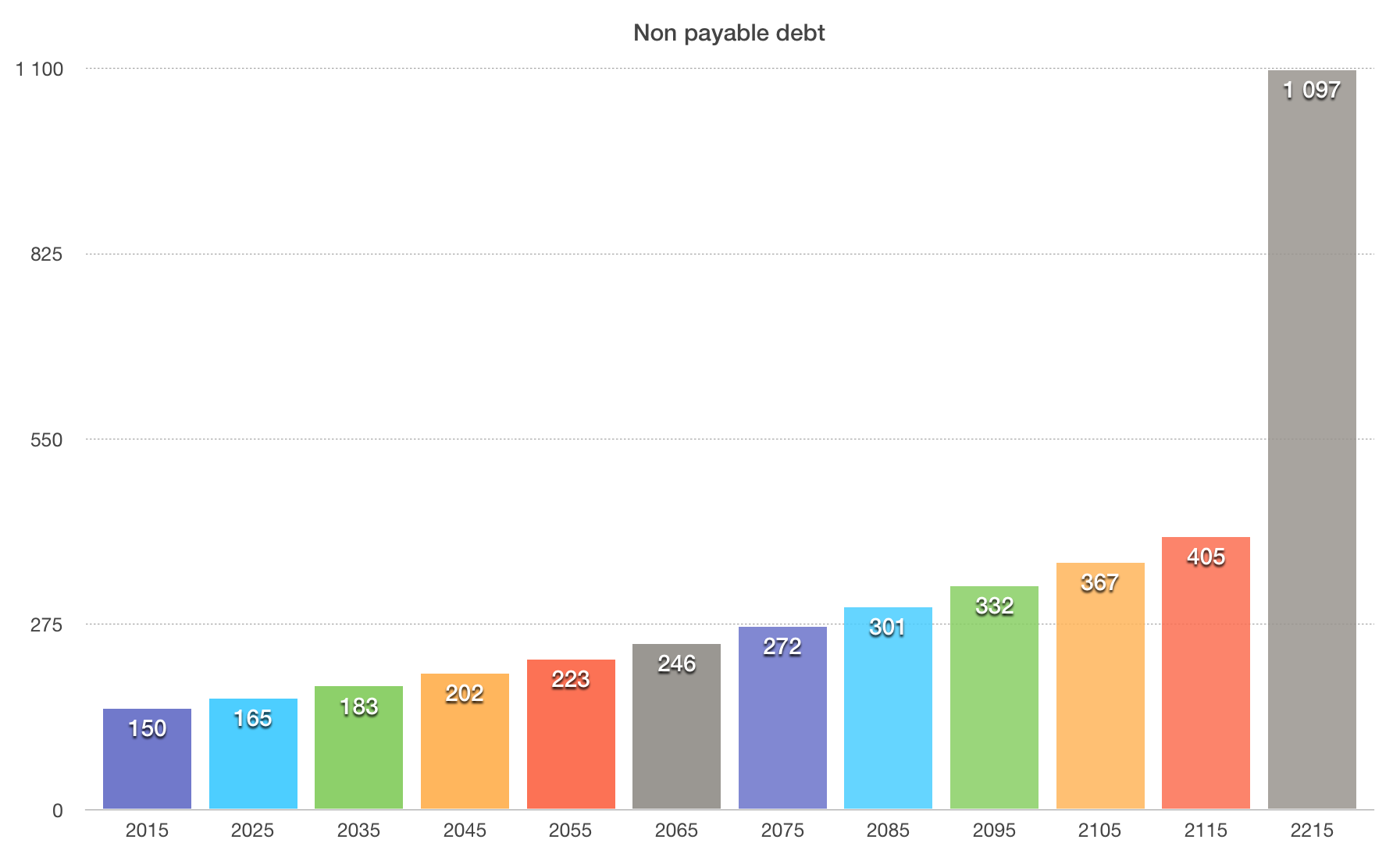

Now both the fable and the algal blooms double the amount on each iteration and as we all know interest rates work in percentages far smaller than 100%. Let’s do the calculations with an interest rate of 1% and only take into account the debt that can not be payed off, which currently stands roughly at $150 trillion. Calculating this with a compound interest calculator gives us the following non payable debt list (results rounded down to the nearest trillion):

- 2025 : $165 trillion

- 2035 : $183 trillion

- 2045 : $202 trillion

- 2055 : $223 trillion

- 2065 : $246 trillion

- 2075 : $272 trillion

- 2085 : $301 trillion

- 2095 : $332 trillion

- 2105 : $367 trillion

- 2115 : $405 trillion

Graphically, it looks like this:

As you notice, the curve starts getting steeper. In about 100 years we add roughly $255 trillion to a debt that can not be payed simply because the money for it does not exist. Another 100 years would bring the total sum to $1097 trillion, adding another mind-blowing $692 trillion to it. This number does not take into account all the the interest on the extra debt that is created because we need to take out loans to pay off existing ones. In reality, the numbers will be quite a lot bigger than is represented here.

The money pump

Apart from creating an ever growing non payable debt, the mere existence of interest on debt also functions as a money pump that channels money from the poor to the rich. It’s built into the system.

Its workings are pretty simple.

-

The Poor Case

When you are poor and are working a job that does not pay well and you want to purchase anything that costs a significant amount of money like a car or a house you’ll need to borrow money. On that borrowed money you need to pay interest. Now it happens to be the case that the lower your capital and your income, the higher the interest rate will be that you pay. That’s because banks follow the logic that if you are poor, that means they run a higher risk of not being payed and therefor they will punish you by making you pay more. If you think this logic is convoluted, you’re not the only one.

So, the poorer you are, the more you will have to pay back and the total sum you need to pay back will always be more than what you borrowed. The chances that you get out of this are fairly small unless you happen to either all of a sudden land a very well paying job, inherit money or win money with the lottery.

And where does this extra money, the interest you are paying, go to? The banks. And these are not owned by the poor.

-

The Rich Case

In this case you have more than enough money to get by. It also means you have quite a considerable amount sitting in the bank accumulating interest and therefor growing exponentially while you’re not even doing anything for it.

Of course, with the interest rates as low as they are today, the value of the money actually decreases just as fast as it grows so, even though this was a very viable option to have your wealth grow 30 years ago that is not so today.

Enter investment bankers. For a small fee, small if you have a large amount of money, they will manage your wealth for you. This is not 100% risk free but in today’s market you can choose amongst several risk portfolio’s so that the chance of loosing everything is rather small. Investing this way gives you a higher return than the standard interest rates and easily pays for the modest fee itself if the invested capital is large enough.

Also, because you probably have some extra cash that you can risk loosing you can invest a small percentage of your wealth in high risk / high gain investments. If this can be spread around enough it’s quite easy to boost your capital significantly.

And since money is created from debt, where does all this money come from? Right, from the biggest pool of debt, and therefor also money, creators in the world, namely the poor.

So, when you have no money, you will create debt, which creates money that will eventually be attracted to the big pools of money at the top of the monetary food chain.

Poverty is build into the system

With the money system as it is designed today, eradicating poverty is a mathematical impossibility. Since money is created out of debt and there is more debt than money, not everyone can have a positive money/debt balance. For everyone who does, somewhere there must be a bigger negative money/debt balance to balance it out.

We are being told that poverty is going down, like in this snippet from an article on the site of the World Bank:

- According to the most recent estimates, in 2012, 12.7 percent of the world’s population lived at or below $1.90 a day. That’s down from 37 percent in 1990 and 44 percent in 1981.

- This means that, in 2012, 896 million people lived on less than $1.90 a day, compared with 1.95 billion in 1990, and 1.99 billion in 1981.

So, the number of people living at or below $1.90 a day has gone down since 1990. What they forget to tell you is that $1.90 today was only worth $1.025 in 1990. So, to have an accurate picture we actually need to know how many people are living at or below $3.53 today. Because that is the indexed value of that $1.90 taking inflation into account.

In a monetary system where money is created from debt with a compound interest on it, poverty can not be eradicated. If we would distribute all the wealth and all the debt in the world, we’d just all be in more debt that we can afford to pay off. The rich need the poor in order to remain rich.

Long term projects? You must be joking!

The fact that money attracts money and thereby becomes an asset by itself is creating a problem for long term projects in the real world. The most obvious one today is climate change. This is a long term project which needs big investments now. These investments will pay of very well by reducing future cost … but only in the long to very long term from the perspective of business owners who think in terms of months or a couple of years at most these days. The major culprit lies in the fact that a short term investment on the financial market often pays of way better than a long term investment in the real world.

Imagine a company van save $1 million a year in 15 years if they invest in $5 million now. Not a lot of top managers say with a company that long anymore today. From the perspective of maximising profit, investing that $5 million in stocks that have the equivalent of an interest rate of say 5% would be more profitable. $5 million invested that way would turn into $10.39 million in 15 years, while investing in the green energy would take 20 years before a break even is reached. So, what do you think is considered to be the best investment for top management?

Say you want to invest in trees. A poplar, which will deliver wood in 10 years costs $10 and will bring you $100 when fully grown. An oak, which also costs you $10 dollars today, takes 100 years to fully grow and will bring you $1000 dollars when fully grown. Seems reasonable and it’s in proportion. Yet, the financial market, with aforementioned stocks that deliver the equivalent of a 5% interest rate trump the investment in oak. Investing the $10 dollars in the stock market instead of in the poplar would only give you $16.29 in 10 years, but investing the $10 for the oak on the stock market would give you a return of $1315, beating the price of the oak.

Every real world long term project is beaten by the return on investment gained in the capital market that way. This means all badly needed but long term projects such as reforestation projects, green energy investments, sustainable production investments, … are hindered by this. Especially in our fast moving world today which is focused on quick and maximised return on investment.

Opposing forces

Interest and the financial market also introduce forces that work against a healthy economy. For an economy to work, money needs to circulate. That means that hoarding money is bad for the economy because that money is just sitting somewhere, doing nothing. Due to the promise of capital gain through interest and financial investments however, more and more money gets locked up in a virtual world where it changes hands without ever creating real value. No goods are traded and no work is done on real world projects that add value to society. It’s all just shuffling around of paperwork.

These two forces, the economic need for money to circulate and the incentive to hoard money in order to gather more money, are detrimental for a healthy economy.

Value for money

In order to support the monetary growth necessary to keep up with the ever growing mountain of debt, value needs to be created in order to limit inflation. This value can be generated through new jobs and/or increased production and the accompanying consumption.

There is a severe discrepancy between value and money however. Some jobs, like lobbying with governments for the interests of large corporations are payed very well as you can see here and here. Often this leads to policy decisions that are against the interest of the public, like the EU dropping pesticide bans under pressure of the TTIP. From the perspective of public intrest, these jobs are detrimental while lining the pockets of already rich organisations. No real added value to be detected. You might also question whether the added value of top CEO’s is in line with their extremely high salaries.

On the other hand, teachers, garbage collectors, farmers, nurses, … all add real value to our society. Their salaries pale when you put them next to the ones from the previous category. And then I’m not even talking about all the people that work in the social sector or everyone who does volunteer work in order to build community or eradicate hunger and poverty.

I would go even further, it pays extremely well to do work that is detrimental to most of us. Doing work that actually adds real value might have you end up with an income that hardly pays the bills.

On the product side we seem to have the opposite. Most of our products are relatively cheap because the real cost is not expressed in its monetary price. That is because the externalities such as the effects of pollution, depletion of resources and the cost of dealing with the end of life of a product is not calculated in the price. We do pay those costs, but not directly. We do it through our taxes which pay for cleaning the water that was polluted and picking up the trash that was generated. We pay for it through increased costs in health care caused by living in polluted environments and breathing in exhaust fumes. It’s payed for by human suffering caused by organisations that underpay and mistreat their employees in low wage countries.

Products that do add in these costs and are produced in environmentally more friendly ways usually cost quite a bit more and are therefor less popular because most of us are strapped for cash. It is understandable that people buy the cheap stuff. It bites us in the ass in more than one way though.

This total imbalance between monetary value and real value scares me.

Due to the pressure our forced economic growth creates, we are pushed into an ever growing and accelerating consumption pattern. Because all that generated ‘value’ that comes from production also needs to be consumed. That’s the reason why we are bombarded with advertisements, urging us to buy new stuff. That’s also what caused planned obsolescence to come into existence. It is perfectly possible to produce a printer that will last you for 20 years. It would mean selling less printers though. And these days everything is done in the name of economic growth, no matter what the cost. Everyone is chasing the money because debts need to be payed off. And in that race, more often than not, what really matters looses out against the lure of more money coming in.

Can there be such a thing as unlimited growth?

Because of the way our money system is constructed we need to keep growing our economy, and that at an exponential rate. Is this possible? Is there such a thing as unlimited growth? The answer is: it depends.

We only have one planet and the resources on our planet are limited. That is to say, depending on the definition of resource, some are. There are many types of resources however.

Physical resources like iron, copper, gold, … are only available in limited supply. We can not keep using more and more of these resources because they will simply run out on us at one point. What we can do however, is re-use them. For that to happen, we need to create production processes that have recycling build in. Something that is not being done on a large scale today.

Resources like wood and food regenerate themselves. There is more room to grow the use of these resources under certain conditions. As long as we make sure we do not use up the resources faster than they can regenerate themselves there is no problem. This means also taking into account the environment in which these resources grow. It’s not enough to not eat more food than we can grow, we also need to make sure our agriculture treats the land in a sustainable way because otherwise the arable land becomes the new bottleneck.

Actually, fossil fuels fall in this category too. Fossil fuels regenerate themselves over time, it just takes a very long time to do so. About 5 million years. If we would spread the use of our fossil fuel reserves over those 5 million years it would turn into an unlimited resource. In reality we will burn through 5 million years worth of reserves in about 200.

There is one category that is available in unlimited quantities. And we can grow it as much as we want. That resource is knowledge. New ideas can be created at no cost. Execution of those ideas may be dependent on resources that are limited in supply but the idea stream itself will be never ending. And yet we treat it as if its scarce. Just look at our patent laws to protect ideas.

Another category where there is a lot of room for growth is in the service sector. Every service that does not need physical resources can grow at an unlimited pace. And for the ones that do need physical resources we need to find a way to use them in a sustainable way.

The question is not whether we can keep growing our economy. Our current growth rate is driven by the way we constructed our monetary system, not by our real needs. Those needs are the needs of the people living on this planet. Through the monetary system we have created we have actually become the slaves of a mathematical model that is flawed and which is driving us down a path of mindless destruction. We need to take a step back and look at what is there, how it is all interconnected and how we can design a monetary system that works for us instead of against us, as it does now.

The role of banks

Banks have a special status in the business world. They are the only organisations that trade in something they want to get as much of as possible themselves. The fact that banks are running our financial system is like handing the management of a cookie store chain over to the cookie monster. Whatever could go wrong with that?

As long as we do not separate the control of our monetary system from the banks, we will continue to have financial crises and the design of our major monetary system will not change. They have everything under control and when things go bad, as history has proved already, governments will bail them out. Except when the bank is in Iceland. Where does this bailout money come from? Either taxes that we pay or through lending from central banks. The latter means more money creation and more debts that need to be payed back.

Conclusion

The dominant monetary system in use today is badly designed. It can only work in an economy that keeps on growing exponentially. Poverty and scarcity of money are built into the system so that achieving this valued resource becomes top of mind for most of people in our society. At least top of mind enough that a shortage or lack of it creates stress on individuals, on relationships and in the workplace. Because there is scarcity in money and it is perceived as a necessity for survival, the pursuing of money too often trumps sustainable action. It gets in the way of taking care of our environment, the unfortunates who are born in poverty and often even the people close to us. We have become slaves to a system that we created ourselves and now seem unable to change. We have even come so far that we think this is just the way things are. But it does not need to be that way. Since we created this monetary system, we can also change it. There are alternative designs that would serve us better, designs that would create incentives for sustainable production, long term planning, community building and compassionate behaviour.

The monetary system we have now is highly competitive in nature. It is also possible to create a model that is collaborative in nature without loosing our current standards of living. In fact, we can even improve our standards of living and way of life through implementing these other models.

The final part of this series will tackle these designs and explain just how they achieve this.

Also published on Medium.

Banks having the power to create money to find a word for. I do find myself wondering “if they didn’t have any of it the moment they journal it into my account, then what is there for me to pay back? I know that’s a bit frivolous but if we look at the IMF creating money to give Greece one wonders why Greece should pay back something that never was. I’m also left to wonder why lending Greece something that never was then gives the lender a sense that they can tell Greece (or any country for that matter) how to conduct their affairs. One way or the other it seems that this massive pile of money – the part which exceeds global GDP is just out there competing with itself, flat out making the next bubble. When that one bursts, or the one after, we might have a chance to bring things back into harmony.