People who know me sometimes jokingly say that some of my typical quotes include “I’ve read an article about that” or “They’ve done research about that”. It’s true, you will regularly hear me say those sentences in random conversations. They reflect my interest and fascination with science.

I’ve also met several people that seem to be resistant to science and what scientists come up with and for a long time this has puzzled me. So I decided to dive into the why behind this resistance. I’ve come up with a couple of conclusions.

- Science is thought to be about hard truths.

- Science and scientists are considered to be the same.

Both these ideas are flawed.

Science vs scientists

It’s a scientist’s job to practice science, just as it is a lawyer’s job to practice law. In both cases we are dealing with people. This comes with all the consequences of being human. Just as some lawyers can be seduced by bribes to bend the rules of law if they think they can get away with it, so will some scientists try to produce results that will make them famous and produce publications. And yes, there have been scandals in the scientific world. But just because there are some scientists that produce fake results, that doesn’t mean science in itself is flawed. That’s like saying that because some car salesmen will try to sell you a bad second hand car that all second hand cars are fundamentally dysfunctional.

And it is the nature of the media to over publish negativity. For every scientist that forges his results so that he/she will be published, become famous or receive extra funding, there are thousands of scientists you never hear of that practice their profession in the spirit of science. This includes having their work, especially when it concerns important discoveries, being reviewed by peers.

No matter which profession you look at, there will always be some rotten apples in the basket. Usually though, most people who do a job out of passion or interest are pretty honest about their work. So also for scientists.

Science and truth

A lot of people think that once a conclusion has been reached in science this has now become a truth. When some time later a contradictory result is published, people loose confidence in science.

In a way science is about truth but not the truth most people think of. It’s about not telling lies, not about saying that some conclusion is now set in stone.

The problem usually begins when a research program delivers some results that are significant enough to make it to mainstream media. Take red wine health benefits for example. Years ago scientists discovered a compound in red wine, resveratrol, that they thought might be linked to a healthier heart. The mainstream media jumped on this and red wine was starting to be portrayed as a miracle drug to prevent heart disease. What they failed to report on was that this was a theory that still needed to be tested. As was found out later, in order to get the benefits from resveratrol by drinking red wine, you’d have to drink about 1000 liters per day. As for the health benefits of other compounds in red wine, the research is not yet conclusive. The belief that drinking about 2 glasses of red wine per day is good for you still holds strong though. The scientific truth is: we’re not sure.

And that last statement is what most people struggle with. Many think science is about figuring out what is known for sure or establishing hard truths. This is a total misconception. Science is more about what we don’t know than what we do know. Scientific truth is more about probabilities than anything else.

What science provides are models of reality. Scientists develop theories about how they think reality works, usually based on observations, and put these theories in models that can then be tested. Good scientists will always try to debunk their own theory. Instead of looking for more cases where the model holds they will try to find cases where the model might fail. The more the model survives these kinds of experiments, the higher the likelihood that the model and therefor the theory holds true.

That means that what was once thought to be true might later be found to not be true because a case has been discovered in which the model fails. And this is something a lot of people struggle with because it’s easier to work with truths that are not falsified later on. The hard part of dealing with truths that can shift is that everything that has been build on a ‘truth’ that has been falsified will need to be questioned again. It’s a bit like building a house on unsteady ground, we don’t like that.

Some theories, like the laws of thermodynamics have withstood enough testing that we can assume they are hard truths that will probably not change. If however an experiment can be conducted that would break down one of these laws, and all factors that would falsify the experiment can be excluded, then even these laws would be susceptible to change. The likelihood for that, although it exists, is very, very small though.

There is no such thing as a failed experiment

A failed experiment, from a scientific point of view, does not exist. For most people an experiment would fail if it doesn’t provide the expected results. This does not hold true in the scientific world though. The goal of an experiment is to produce data, even if that data is completely the opposite of what is expected. A fine example of that is when a researcher expected flatworms to die sooner when they were producing more free radicals. He found out that the opposite is true, thereby falsifying a whole slew of beliefs about ageing.

What needs to be questioned however is whether the conclusions drawn from the data is correct and whether the data is useful. Good scientists do both.

One field where both are being put under scrutiny for example are psychology and the social sciences. Most experiments in human behaviour are conducted on western university students for the simple reason that they are readily available to researchers. The problem with this is that the conclusions only really has value for the group that participates in the studies. The same experiment with Chinese farmers might have a different outcome. It would be easy to jump to the conclusion that all these experiments are now worthless but it’s not as simple as that either. Until we repeat them with different groups of participants, the only thing we can say for sure is: we don’t know.

Publication bias

Something that also vastly skews the general public’s idea of what science is all about is that experiments that do not produce anything interesting, so called ‘null results, are not published.

This creates the idea that scientists almost always conduct experiments with an interesting outcome. There are some implications to that view. Many policy makers also seem to hold this view and apparently conclude that therefor science is all about creating predictable results. Getting funding for fundamental or basic research these days becomes harder and harder. That’s because this type of research research has no predictable result.

Fundamental research is all about following paths which no one knows where they lead to, out of mere curiosity. It’s stepping in the realm of that which we don’t know we don’t know. This can lead to findings that are very valuable though.

The other downside of not publishing null results is that a lot of time is wasted on repeating experiments that have already been done.

Correlation vs causation

A trap that many fall into is to confuse correlation with causation.

Correlation exists when two things are related to each other. For example: the number of people in a country is correlated to the number of couples in a country. They rise and fall together.

Causation is when one thing is the cause of something else. For example: the more tornadoes, the more damage in the areas where the tornadoes go through. In this case the tornadoes are clearly the cause of the damage.

To have causation, correlation is necessary. If the amount of damage would not be in relationship to the number of tornadoes then the tornadoes could not be the cause of the damage. There are many circumstances though where correlation exists without one being the cause of the other. Some of the funnier ones:

- The divorce rate is Maine is correlated to the margarine consumption in the US

- Consumption of mozzarella in the US is correlated to the civil engineering doctorates awarded

- …

The many aspects of science

As you have probably realised by now, science is not a black and white thing. Good scientific conduct is about constantly questioning things and trying to falsify your own conclusions. It’s about working with probabilities instead of truths. It’s about being prepared to rethink everything you believed to be true because the data tells you to.This is contradictory to what most of us do in our daily lives. We tend to look for proof which supports our belief, not proof that would undermine it.

It will never be flawless because it’s conducted by people. I do believe that the scientific world does its best to produce good results though, just as I believe that most car mechanics really do their best to keep my car going. And science has brought us better health, better transport, the internet, insights in human behaviour, increased production capabilities, … You might say not all inventions have been beneficial and you are right. It’s not the fault of science itself though but of the people who abuse the findings. You can use a chair to kill someone but that hardly means we need to get rid of chairs.

Scientific reasoning is a way of thinking that I find very valuable because it introduces openness. If we are willing to question our ‘absolute truths’, we develop critical thinking and become open to new solutions we didn’t think were possible. We also open up to the fact that the other just might be right without blindly believing everything that we are told. It makes us curious and it’s a workout for our brain.

Some of you might think that scientific reasoning is all about cutting up the whole in parts and the study the parts in order to comprehend the whole. Or, to put it in other words, reductionist thinking. For a long time this has been mostly true but things are changing. For years now more and more scientists have started to embrace the fact that studying the parts is not enough, the whole also has to be studied in order to comprehend it.

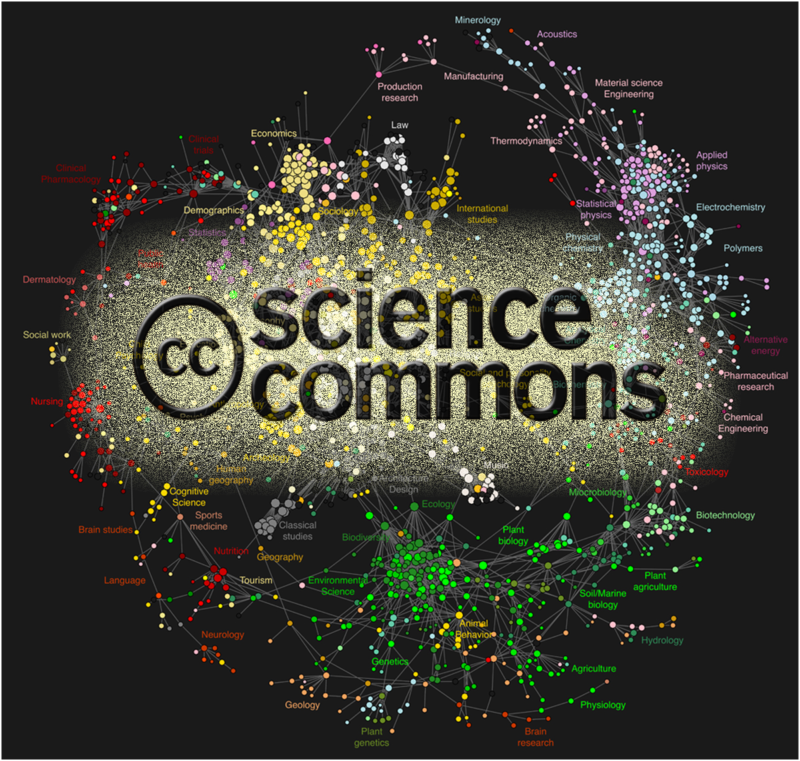

The number of scientific fields is also incredibly vast. A lot of us immediately think of physics or chemistry when the word science is mentioned. Psychology, IT, health, transport, politics, economy, law, culture and many more topics are also areas where science can and often does play a significant role though.

To get insights in complex challenges we need to acquire some solid thinking skills. Intuition and common sense, although very valuable, will only bring us so far and they don’t always work, especially not when problems become very complex. If you are willing to be confronted by how fast we sometimes reach conclusions that are utterly wrong, read this article. I always thought my thinking was pretty solid but learned that I jump to conclusions more often than I assumed. It was a valuable lesson.

Also published on Medium.

No comment yet, add your voice below!